Foundations of Fiction: How to Use Dialogue to Reveal Character

Here’s a riddle: How does a writer use dialogue to reveal who their characters are, including their backstory, without stilted monologues and corny set-ups?

Answer: Stealthily. (Oh, is that all, you ask?)

Dialogue. Is. Hard.

I’ll say it louder.

Dialogue. Is. HARD.

Why is it so hard? It has a heavy load to carry in a story, namely, it must:

- Propel the story forward

- Reveal character

It is NOT:

- A dumping ground for exposition

- A dumping ground for mindless chit chat

- Meant to sound too realistic

“Reveal Character” and “No Exposition” seem to be totally at odds with each other, probably making you think, “It’s too difficult. I don’t know how to do it.”

Like most things, once you get a handle on what it should look like, and you practice, it will get easier.

There are three ways to use dialogue to reveal character:

- Through another character.

- Directly from the character.

- Through internal dialogue (both from other characters and the character themselves).

In this Foundations of Fiction: Dialogue, we’ll explore how to REVEAL CHARACTER.

Who is the Character?

When it comes to revealing character in dialogue, start by asking yourself two important questions: who is the character and what do you want readers to know about them?

Of course, some biographical detail is good—hometown, job/career, education, etc. However, characters are so much more than what they do. Part of your job as their creator is to understand what motivates them and uncover what their quirks/flaws/strengths and vulnerabilities are.

In other words, what makes them tick?

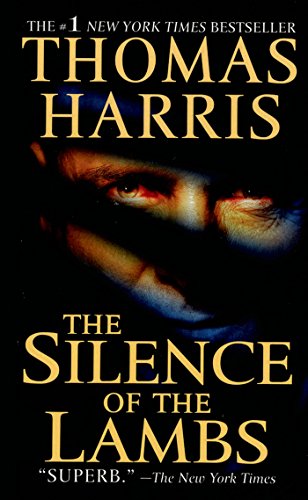

Let’s use Clarice Starling, one of fiction’s most famous protagonists, to examine how dialogue illustrates who she is and what makes her tick.

Here’s the name, rank, serial number on Clarice Starling from “Silence of the Lambs,” by Thomas Harris: She’s an FBI trainee whose father was a marshal in her West Virginia town. He was killed in the line of duty when Clarice was ten. Her mother was unable to care for her and Clarice was sent to live with a relative, and later to an orphanage. She attends the University of Virginia, double majoring in psychology and criminology. While in school, she spends two summers as a counselor in a mental health center. Her eventual mentor, Jack Crawford, is a guest lecturer in criminology at UVA, which spurs her to join the FBI.

This is all great (and necessary) biographical information about Clarice. However, it doesn’t tell us anything about who she is as a person, what motivates her, what her desires are. If the above was all we ever found out about Clarice, she’d be pretty boring to read about.

Revealing Character via Another Character

One of the ways to reveal to the reader who Clarice is as a person, is to give the job to another character. Harris cleverly assigns the task to the book’s antagonist, forensic psychiatrist Dr. Hannibal Lecter.

Lecter sums up Clarice as follows:

When he spoke again, his tone was soft and pleasant. “You’d like to quantify me, Officer Starling. You’re so ambitious, aren’t you? Do you know what you look like to me, with your good bag and your cheap shoes? You look like a rube. You’re a well-scrubbed, hustling rube with a little taste. Your eyes are like cheap birthstones—all surface shine when you stalk some little answer. And you’re bright behind them, aren’t you? Desperate not to be like your mother. Good nutrition has given you some length of bone, but you’re not more than one generation out of the mines, Officer Starling . . . Let me tell you something specific about yourself, Student Starling. Back in your room, you have a string of gold add-a-beads and you feel an ugly little thump when you look at how tacky they are now isn’t that so? All those tedious thank-yous, permitting all that sincere fumbling, getting all sticky once for every bead. Tedious. Tedious. Bo-o-o-o-r-i-ing. Being smart spoils a lot of things, doesn’t it?”

Starling raised her head to face him. “You see a lot, Dr. Lecter. I won’t deny anything you’ve said.”

From Lecter’s blistering assessment of Clarice, we learn she’s fairly unsophisticated, but trying so hard not to be (just a few pages earlier, Lecter comments that, “You brought your best bag, didn’t you?” and we learn from Clarice, that yes, she saved for the “classic, casual handbag,” and it is indeed “the best thing” she owns. And Lecter eviscerates her for it.) She’s smart, bright, and ambitious, though these attributes are both a pain and a privilege. She’s terrified of being like her mother and desperate to scrub the sheen of her hardscrabble background from her skin. But despite her education and pursuit of a professional career, it’s always there, just under the surface.

Revealing Character via One-on-One Conversation

Approach number two to revealing character via dialogue is to have the character tell another character something about them. Here, Clarice will divulge some of who she is to Lecter (“Quid pro quo”). She wants information from him regarding a serial killer she’s tracking who’s kidnapped a senator’s daughter, which he’ll provide, only if she shares tidbits about herself in exchange.

Here are some excerpts from some of their many exchanges in which Clarice peels back the pages of her backstory and her personality:

“Maybe I’ll trade for a piece of information about you? Yes or no?”

“Let’s hear the question.”

“Yes or no? Catherine’s waiting, isn’t she? Listening to the whetstone? What do you think she’d ask you to do?”

“Let’s hear the question.”

“What’s your worst memory of childhood?”

Starling took a deep breath.

“Quicker than that,” Dr. Lecter said. “I’m not interested in your worst invention.”

“The death of my father,” Starling said.

“Tell me.”

“He was a town marshal. One night he surprised two burglars, addicts, coming out of the back of a drugstore. As he was getting out of his pickup he short-shucked a pump shotgun and they shot him.”

Later, Lecter asks her to elaborate on the death of her father…

“Tell me a detail you remember from the hospital.”

Starling closed her eyes. “A neighbor came, an older woman, a single lady, and she recited the end of “Thanatopsis” to him. I guess that was all she knew to say. That’s it. We’ve traded.”

“Yes we have. You’ve been very frank, Clarice. I always know. I think it would be quite something to know you in private life.”

“Quid pro quo.”

Later, Clarice tells Lecter about the night she ran away from her relative’s farm with one of his horses:

“What made you run away with the horse?”

“They were going to kill her.”

“Did you know when?”

“Not exactly. I worried about it all the time. She was getting pretty fat.”

“What triggered you then? What set you off on that particular day?”

“I don’t know.”

“I think you do.”

“I had worried about it all the time.”

“What set you off, Clarice? You started what time?”

“Early. Still dark.”

“Then something woke you. What woke you up? Did you dream? What was it?”

“I woke up and heard the lambs screaming. I woke up in the dark and the lambs were screaming.”

“They were slaughtering the spring lambs?”

“Yes.”

We later learn what fundamentally drives Clarice. Or, what makes her tick. . .

“You still wake up sometimes, don’t you? Wake up in the iron dark with the lambs screaming?”

“Sometimes.”

“Do you think if you caught Buffalo Bill yourself and you made Catherine all right, you could make the lambs stop screaming, do you think they’d be all right, too and you wouldn’t wake up again in the dark and hear the lambs screaming? Clarice?”

“Yes. I don’t know. Maybe.”

The death of her father and screaming lambs are what drive Clarice. She couldn’t save her father. She couldn’t save the lambs. But maybe, she can save Catherine.

Revealing Character through Internal Dialogue

The third method for revealing character is through internal dialogue, which is the inner voice of the character. This is where we learn more about how the character sees themselves and how their observations inform that view.

Here are three excerpts of Clarice’s internal dialogue, revealing who she is:

Paperwork. Clarice Starling’s self-interest snuffled ahead like a keen beagle. She smelled a job offer coming—probably the drudgery of feeding raw data into a new computer system. It was tempting to get into Behavioral Science in any capacity she could, but she knew what happens to a woman if she’s ever pegged as a secretary—it sticks until the end of time. A choice was coming, and she wanted to choose well.

Here, Clarice’s ambition is on display. She wants to be in the Behavioral Science Unit. She wants to climb the ladder at the FBI. But at what cost? Is this mystery assignment she’s being offered worth being slotted into a hole she can never climb out of?

***************************************

Dammit, she should have read him better, quicker. He might not be a total jerk. He might know something useful. It wouldn’t have hurt her to simper once, even if she wasn’t good at it.

In the second example, Clarice berates herself for not kissing up more to Dr. Chilton (head of the sanitarium where Lecter’s being held) after he makes an awkward pass at her. She’s not good at playing coy or dishing out insincere flattery.

****************************************

Some of the things Lecter had said about her were true, and some only clanged on the truth . . . she hated what he’d said about her mother and she had to get rid of the anger. This was business.

In the third example, she acknowledges the truth of Lecter’s assessment of her. However, she has to put the sting of his insights aside, because she has a job to do – and she never lets anything get in the way of that.

So, through three distinct dialogue tactics, we’ve learned a LOT about who Clarice Starling is. These characteristics are spread out over the course of the story, not dumped on us all at once. Harris continually unravels the layers of who Clarice is, what he wants us to know about her and how he wants us to learn that information. Revealing her character is not done in one expository dump, but methodically and carefully.

The Takeaway:

As you start to build your fiction foundation, a phrase which will sear itself into your consciousness over time is “character drives plot.” In other words, understand who your characters are and how they will act and react to the events in your story.

Uncover who your character is by learning their backstory, their ticks, quirks, fears, needs, and wants and determine how to encapsulate that information in dialogue. Decide how and when you want to reveal those details to the reader. Tap the other characters in your protagonist’s world – including the antagonist – to tell us who they are through precise dialogue exchanges. Avoid expository dumps. Avoid telling the reader everything about the character upfront. Remember the effectiveness of internal dialogue.

How do you use the above three methods to craft your dialogue?